Exposing the tactics of public spaces to welcome and ward off for London Festival of Architecture

20th century design taught us that good design is as little design as possible. The same is true of defensive design, which, for many of us, is barely noticeable. Unless, of course, you’re the one it’s designed to keep away.

Sometimes referred to as hostile architecture, this is urban design that manipulates how a space can be used — and by whom. You might be homeless, trying to find some rest. But armrests on benches make it too uncomfortable to lie down. Or pigeon perches might be covered by a row of spikes. None of this is an accident.

For this year’s London Festival of Architecture, DNCO hosted Uncivic Space, an uncomfortable exhibition that put these subtle strategies under the spotlight.

Here are five things to watch for in the urban spaces around you. Does hostile architecture make an intelligent design solution? It all depends on who you ask.

Sound

Sound can be a powerful deterrent, especially when not everyone can hear it. The Mosquito Anti-Loitering Alarm emits a high-frequency noise that evades the ears of most adults, but creates an uncomfortable ringing in the ears of teenagers. The message is clear: if you can hear this, you’re not welcome here.

What’s defensive to some is enjoyable to others. In Canada and the UK, several public places resort to playing classical music in an attempt to reduce anti-social behaviour. Transport for London rolled out a scheme to reduce crime through music, and the results have been so favourable that it will be extended to 40 further locations. For stressed-out commuters, this is a good thing: out of 700 commuters surveyed, TfL found, “they overwhelmingly agreed that hearing classical music made them feel happy, less stressed and relaxed”.

There are even more bizarre examples: in Florida, Baby Shark is blared on loop outside an event venue, a decision that veers a little too close to methods used to wear down victims of psychological interrogations. Other than that, music can be an effective and harmless way to reduce crime and loitering in certain areas. But for young people living in areas where the Mosquito Alarm is used, it raises questions if they are being punished just for being able to hear it.

“Pain is one of the most recognisable forms of defensive design. If it hurts, you’re not meant to be there.”

Pain

Pain is one of the most recognisable forms of defensive design. If it hurts, you’re not meant to be there. This is especially true if you’re homeless, where a number of techniques communicate where rough sleepers aren’t welcome. Spikes on the ground can be seen outside buildings around the world. Spikes or shards of glass often make up the top of fences, making climbing painfully impossible.

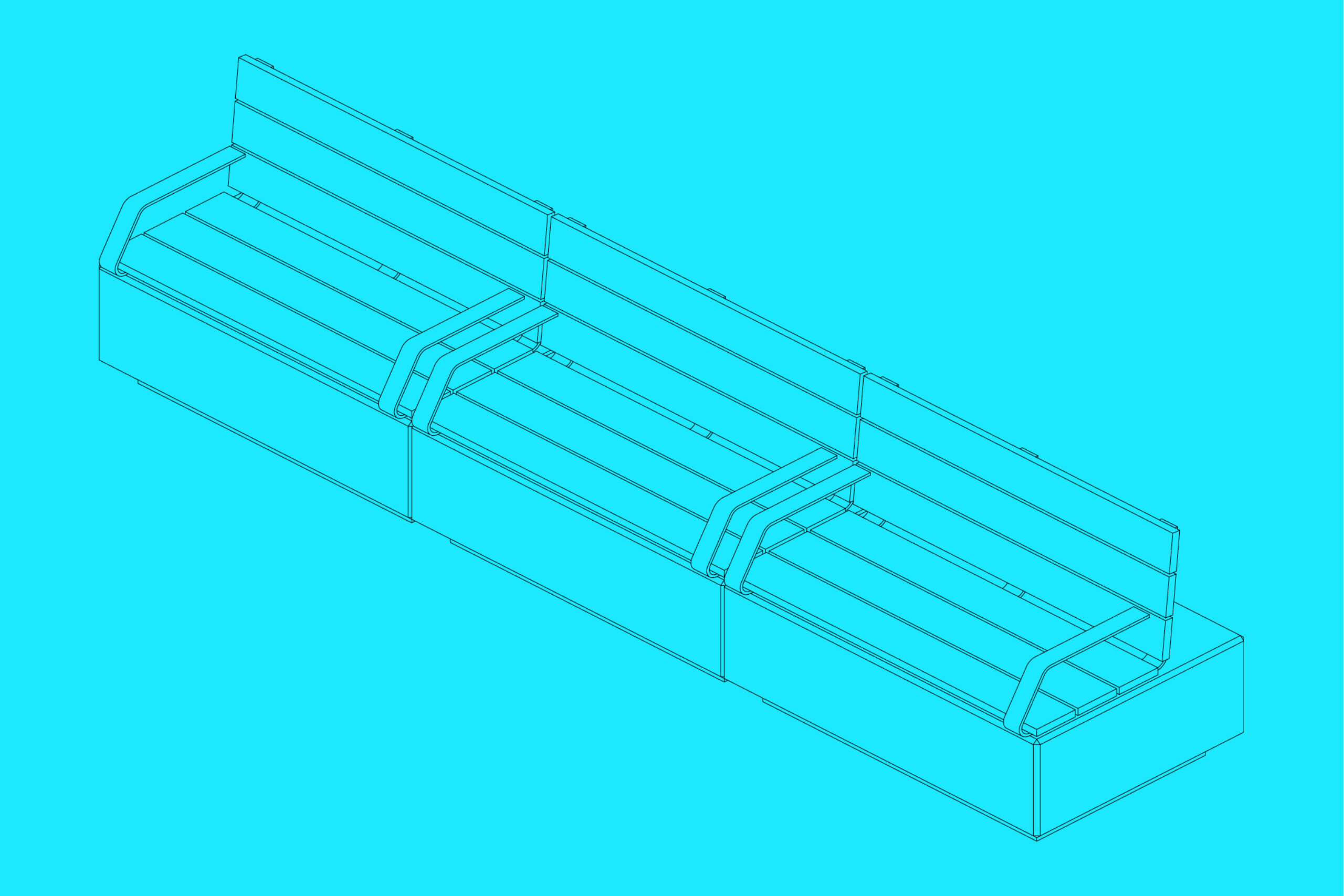

But one of the key ways that pain is used is through an object that many of us find to be quite pleasant: the park bench. Public benches are a crucial part of the urban fabric. They’re a key design feature of friendly cities and can encourage city dwellers to interact with one another. But if you look closely, many have been designed to be uncomfortable for people to lie down. This might be through the use of armrests, uneven surfaces or the size of the object itself. At bus shelters in London, the slanted bench has a clear message: you’re welcome to perch here, but only for a few minutes.

Humans aren’t the only ones affected by painful design interventions.Anti-pigeon spikes are used around the world to deter them from roosting in high-footfall public spaces. But what deters one species might help another: seagulls have been observed building nests wedged between anti-pigeon spikes.

Obstacles

Skateboarders, for better or worse, get a lot of flack for being disruptive in the public realm. To dissuade them from using public stairways to practise their railslides, you’ll find many railings are designed with a series of brackets that interrupt the smooth downward slope. If you see unexplained grooves or metal brackets disrupting concrete surfaces, it’s often a message to skateboarders to go elsewhere.

With more and more cities creating designated parks for skateboarding, rollerblading and BMXing, the idea of skateboarders as a public nuisance is starting to feel dated. Skateboarding creates community and it’s a physical activity that’s much healthier than sitting on the sofa. But that hasn’t stopped these interventions from keeping a clear barrier between pedestrians and thrill-seekers on wheels.

Bollards are another obstacle used in urban space. This time it’s less about preventing a public nuisance and more aboutpublic safety. You might notice these peppering pedestrian areas as a way to prevent cars from driving into areas with high footfall. In Times Square a series of 3D printed anti-terrorism benches have been installed — a perfectly pleasant place to sit otherwise, but can act as a fence to stop moving cars from entering the space.

“With more and more cities creating designated parks for skateboarding, rollerblading and BMXing, the idea of skateboarders as a public nuisance is starting to feel dated.”

Surveillance

People in the UK are among the most watched on the planet. In London, there is one CCTV camera for every 13 people. It means that whatever we’re doing, whether we’re running a red light or just going about our day, there’s a good chance that some of it is being recorded.

Sometimes it’s just the presence of cameras that can prevent crime. It all comes back to the perception of getting caught. This idea has spurred the production of fake CCTV cameras. They’re not recording anything, but they’re designed to look the part.

The perception of getting caught is a powerful tool that can be wielded not just through fake cameras. Natural surveillance is an urban design technique that calls for open spaces with ample visibility. It also comes down to how we zone our cities — if a place is busy around the clock, it can prevent crime because there are more people around to see it.

Humans themselves can also be a form of defensive design, just look at the security guard. They’re employed to maintain a feeling of safety, but at what cost? Many visible minorities are made to feel uncomfortable by lurking guards. And it often isn’t clear: what is and what isn’t acceptable behaviour?

Surveillance is fraught with controversy. It raises concerns over privacy and effectiveness, harking back to the 18th-centuryPanopticon — a circular prison design where prisoners are being watched, but couldn’t see who was watching. On the other hand, if a fake camera can prevent a break-in in a non-violent way, isn’t that a job well done?

Light

When was the last time the presence of lighting prevented you from doing something? Lighting can be a discrete form of defensive design, but as with most of these examples, it depends on who you ask. In parts of the UK, pink lighting is used to deter teenagers from loitering, because the pink colour highlights their spots.

Blue lighting is also widely used as a drug-prevention measure in tucked away public spaces like toilets and underpasses — the colour makes it extremely difficult for drug-users to find their veins. It won’t stop drug-use altogether, but it might encourage users to seek out safer injection sites. to

To people who aren’t using, the blue light can have a calming effect. It’s used in train stations across Japan to alleviate stress and prevent suicide. A study from 2013 showed the blue lights reduced suicides by 84%, a success rate that inspired stations in the UK to follow suit.

Urban lighting has long been associated with public safety. In Haussman’s Paris, street lighting was paid for with the police budget, and it was thought it would make the streets less conducive to starting an uprising. On the other hand, lighting can offer a form of natural surveillance. There are contradicting accounts of the efficacy of lighting, but well-lit public spaces create a feeling of safety, making the city a more comfortable one to be in.

Uncivic Space was an exhibition at DNCO in June 2022, running as part of the London Festival of Architecture.