The benefits and pitfalls of keeping Portland weird

Like all the best stories — David and Goliath, Sophocles’ Antigone, You’ve Got Mail — this is the tale of a battle of the individual against the corporate giant. In this case, our hero is no turtlenecked Meg Ryan but Steve Bercu, an independent bookshop owner. With news of a new and shelf-bustingly huge Borders opening around the corner, Bercu printed a few thousand bumper stickers with a simple but powerful rallying cry: ‘Keep Austin Weird’.

Wait. Austin? That’s right: Portland’s infamous city motto ‘Keep Portland Weird’ is in fact Texan in origin. Weird, right? This simple two-fingered, stick-it-to-the-man sentiment certainly chimed with the alternative-living West Coast city, but it also usurped and took on greater resonance here because it poses an important Portland-pertinent question — is there another way of creating the commercially successful American city? A city experience that goes — wait for it — beyond Borders.

By early-2000s American city standards, Portland was definitely weird. An openly gay mayor, excellent public transport, citywide cycling, citywide recycling — the initial adoption of Keep Portland Weird to protect the interests of small businesses was being extended to city policy and planning. It was an articulation of a different way of living: and a different way of imagining the urban experience.

Policy makers made no secret of their derision of the LA model and rejection of any attempts to replicate its ‘infinite chokehold freeways and no-centred-ness.’ Its medical students, for example, are known to travel campus-to-campus via gondola.

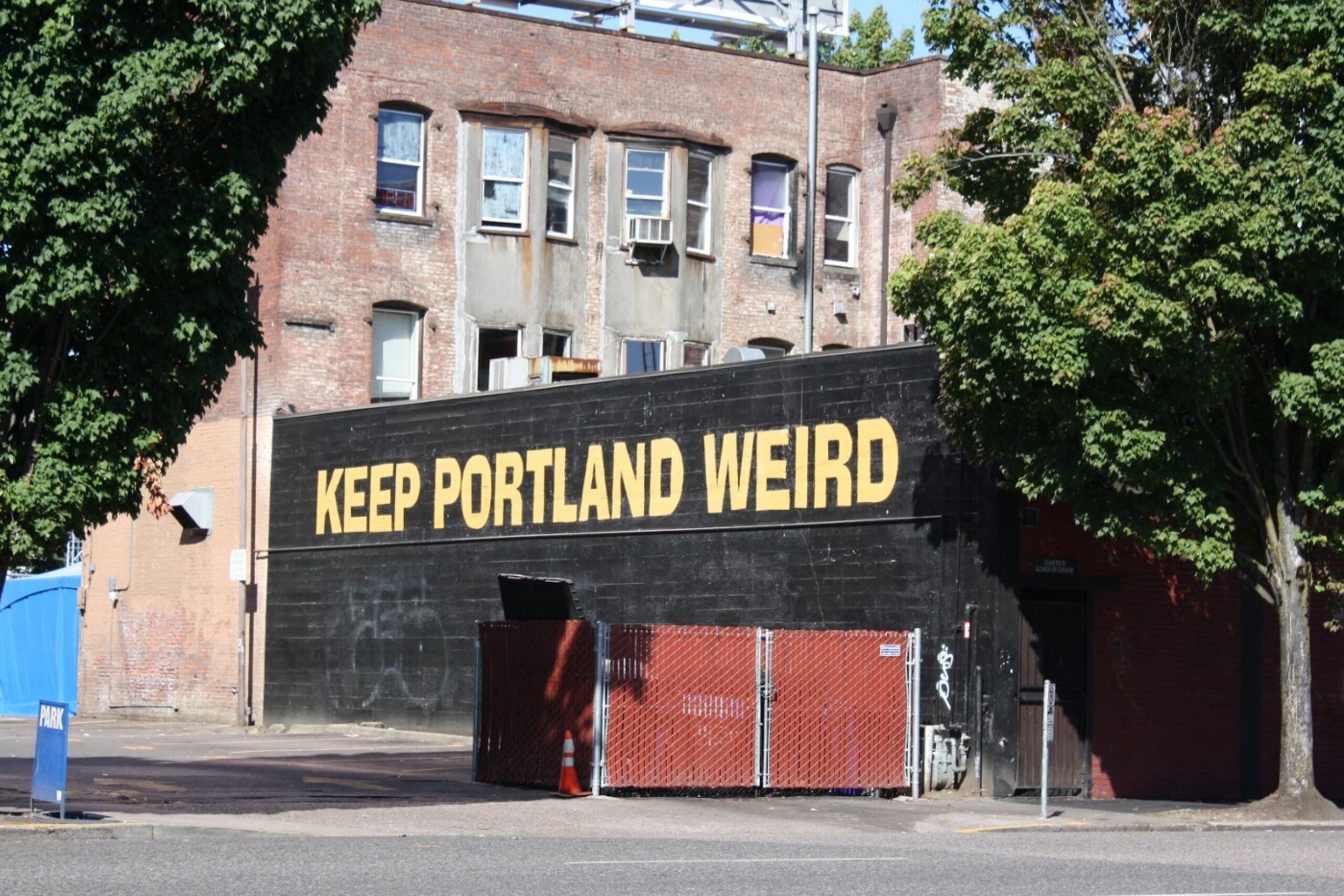

Economically too, the city was noted as an activewear cluster and had a reputation for its ‘Obama-era zeitgeist, emerging technology, DIY mentality and organic movement.’ Keep Portland Weird — by this point on 18,000 bumper stickers around the city and emblazoned on the side of a building with a 30-foot long mural — had gone beyond alternative lifestyle choices and towards economic strategy.

In completely over-simplified terms, there are two economic benefits to being weird. Firstly, to be weird is to be free to take a different view. It’s to be unafraid: it’s about having an innovative mindset. ‘In a turbulent economy, being different and being open to new ideas about how to do things are remarkably important competitive advantages’ City Observatory founder Joe Cortright noted back in 2010.

Weirdness also has cultural currency and it marks your city out as a more defined, special, rare product. This is about differentiation in the marketplace. It might not be a lifestyle and worldview that appeals to everyone but there’s power in offering an alternative. Perhaps it’s time to talk about Portlandia.

The hit comedy show from SNL’s Fred Armison and rocker Carrie Brownstein launched in 2011 and frames everything I understand to be Portlandian. It’s a tongue-in-cheek-smoking-a-doobie look at the laidback culture of the city in the time of the new economy and eco living. For me, Portland will forever be a delightful superfood-infused mash-up of tech, punk and mysticism. Drone helmets and feminist literature. Sanctimony and armpit hair. Breakfastizing and an existential questioning of the difference between our online experiences and our physical lives.

Launching its eighth and final series, Portlandia has proven to be a successful recipe for the show. But can the same be said for the city?

Weirdness and commercialism are certainly unconventional bedfellows. Critically so, think the Willamette Week — an alternative weekly in Portland — who recently declared that ‘Old Portland is dead.’ The lambasting piece stated that longtime residents and their dearly held weirdness are being replaced by ‘sleek condominiums and chain stores. Rents have skyrocketed and traffic is gridlocked.’

The cause? Their survey said: ‘was it the day tourists insisted on taking selfies in front of the artisanal ice-cream store Salt & Straw indifferent to the crime tape from a recent shooting nearby? Or was it when a luxury development distributed a promotional video of tenants drinking gluten-free alcohol on the terrace? Turns out, it was neither. After hundreds of voters weighed in, the results came back. Old Portland died on January 21, 2011 — the day Portlandia debuted.’

Herein lies another important word to consider in the city motto: keep. It presents the city with a tricky conundrum: how do we keep Portland weird without being protectionist? But, I’d say, this friction is an excellent thing: it’s a conversation that will continually make policymakers and citizens consider how they want to be weird.

That’s the beauty of Keep Portland Weird. It’s not just a bumper sticker or an economic strategy — it’s a powerful piece of purpose. A driver for appropriate decision-making. Consider that sentiment as I introduce you to the city’s mascot; a unicycling, kilt-wearing, Darth Vader mask-wearing, bagpipist of fire known as The UniPiper. How weird, how Portland.